On our homestead, we generate our own electricity. We do this because the original builders of the homestead set it up that way, because we’re far beyond municipal utilities, and because we like taking responsibility for our own power.

Beyond that, there are many good reasons for either separating one’s family from the electrical grid, or at least creating back up electrical generation that doesn’t require additional power.

Electrical interties are a hot subject in Southeast Alaska, where high utility costs generate (sorry!) a lot of interest in connecting bush communities to power centers, like Juneau and Sitka. Our town is one, although the local needs require burning diesel fuel some of the time.

Interties, like so many aspects of modern life, work very well, provided everything goes as planned. When things don’t go as planned, it can be a disaster.

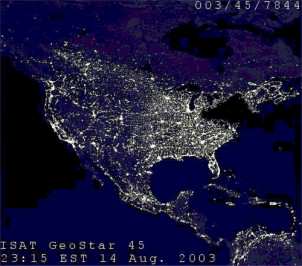

A satellite image of the northeastern U.S. taken by the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program on Aug. 14, 2003 at 9:03 p.m., when a blackout affected 50 million people. (Image: NOAA/DMSP.)

For instance, 10 years ago yesterday, on August 14, 2003, the northern tier of the contiguous U.S. and southeast Canada experienced the largest “cascading” power blackout in the history of the world. It affected 50 million people!

David Newman is a physics professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks who studies interconnected systems that fail catastrophically, including power transmission grids, intercity cars and trucks halted during traffic jams, and huge communications systems like the Internet, which can be disrupted by a single computer worm.

“Events like [the blackout of 2003] happen for two reasons: we sit on the teetering edge of collapse with our power demands, plus we’re interconnected,” Newman said in an interview with Ned Rozell, science writer with the Geophysical Institute,

University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Most cities don’t have power generators large enough to provide enough electricity during peak demand periods.

“If we had to supply each city on its neighboring power plants in times of peak need, forget it,” Newman said.

To satisfy the call for power at peak times, electrical utilities buy power from other places. A few large regions of the U.S. are connected. The intertwined nature of the system makes it possible to share electricity, but the connected lines also make the system prone to avalanching power outages, which, like the 2003 blackout, cut electricity to 50 million Americans and Canadians in nine seconds.

Newman says that one problem with the electrical system of North America is a 2% increase in U.S. power demand each year and a lack of simultaneous upgrades to power generators and transmission lines.

“Couple this to some hot summer days and we have a system sitting on the edge waiting for something to push it over,” Newman wrote in an editorial he submitted to The Washington Post.

Newman said that while it will be possible to prevent the specific problems that caused the 2003 blackout, other, unpredictable problems as small as a squirrel chewing through insulation at a power-transmission substation will continue to threaten the system. In the short run, people can manage the power problem by installing more power wires to spread out the load and by increasing the capacity of power plants. In the long run, as Newman wrote in another paper “major disruptions from a wide variety of sources are a virtual certainty in a complex system.”

Recently, there has been speculation that a well-placed virus might wreak havoc on a largely computer-controlled inter-tie system.

But what can you do?

Material for this post was provided as a public service by the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the UAF research community.

I worked in power production for years and am fully aware of all the problems with our nations grid: It is basically a catastrophe waiting to happen 🙁